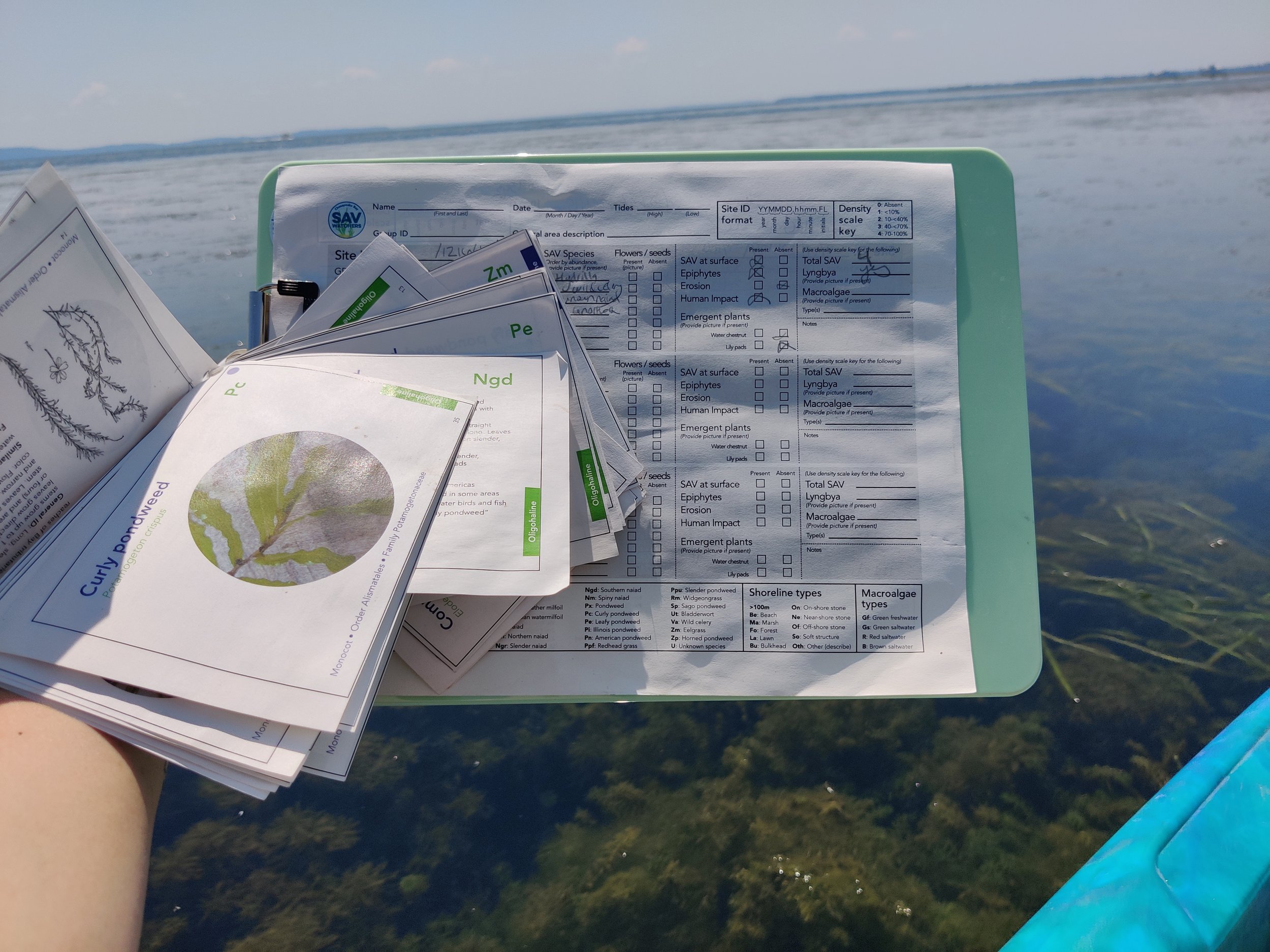

The Havre de Grace Maritime Museum works in partnership with the Chesapeake Bay SAV Watchers - a program designed to provide volunteer scientists with engaging and educational experience with submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) while also generating useful data for Bay scientists and managers. This is the first official SAV monitoring program for volunteer scientists developed by the Chesapeake Bay Program.

What is submerged aquatic vegetation (SAVs)?

SAVs are underwater grasses that play a vital role in the greater ecosystem of the Chesapeake Bay. They are flowering, vascular plants that, depending on the species, survive in freshwater, saltwater, or brackish water. Just like all other plants, they photosynthesize - meaning they require sunlight in order to turn carbon dioxide and water into energy and oxygen.

SAVS, like all living things, are sensitive to changes in their environment. SAVs in particular are sensitive to light availability, temperature, salinity, water currents, water quality, and the substrate in which they grow.

There are 500 known SAVs worldwide! In the Chesapeake Bay, there are 20 species known.

Why are SAVs important?

SAVs are necessary for sustaining marine, brackish, and freshwater ecosystems. They provide habitat for benthic invertebrate species, blue crabs, shellfish, amphipods, isopods, and shrimp. Invertebrates use SAVs for shelter and anchorage. Algae lives on the surface area of SAVs, which provides food for fish and predators. Fish use SAVs as shelter, nursery habitats, and as a buffet of detritus and smaller organisms. Waterfowl eat seagrasses, as well as the organisms that live in seagrasses.

SAVs absorb carbon, and fascinatingly, store carbon even after death. Carbon sequestered by SAVs stay in the sediment rather than being released, which is what happens with terrestrial plants. All carbon and carbon dioxide stored is not released back into the ecosystem, which is hugely important in the fight against climate change. In fact, the Chesapeake Monitoring Cooperative states that underwater grasses are responsible for 10% of all carbon buried in the oceans, which is twice as much as the world’s temperate and tropical forests!

SAVs suck up excess nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus from the water column, which helps improve water quality, and protects against toxic and harmful algal blooms.

SAVs trap sediment, which if suspended in the water column can make it hard for fish to breathe, and can prevent underwater plants from photosynthesizing.

SAVs protect shorelines from erosion by slowing waves and tides.

What threatens them?

The Chesapeake Monitoring Cooperative reports that over the last 100 years, we have lost 25% of seagrasses and large amounts of SAVs. Threats to SAVs include disease, storms, and other human events. Poor water quality as a result of pollution threatens SAVs, and climate change has led to die-offs. Damage from boat propellers, dredging, and shoreline armoring has further depleted SAV populations.

What are we doing about it?

We have joined the Chesapeake Bay SAV Watchers to monitor SAV diversity and growth throughout our piece of the Chesapeake Bay. We report our findings to their larger data base, as part of a citizens science initiative to determine the state of SAVs. SAV monitoring and protection is an all-hands-on-deck endeavor. And we need your help!

To learn more, you can visit the Chesapeake Monitoring Cooperative Website here.